Source: Paramount Pictures./ Fair use.

This article was published in Spanish in the Cuaderno de Cultura Cientifica (CCC) under the title “LaLa Hisotria de tu Vida llegada y el cálculo de variaciones,” under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Except for the English translation, no changes were made to the original article. Published with permission of CCC.

The author, Gisela Baños, is a science, technology, and science fiction communicator.

In 2016, the heptapods descended in their immense ships to Earth’s surface and forced a humanity incapable of communicating with itself to do so with an entirely different species… at least in the movies. Shortly after its release, Arrival rightfully earned a place on virtually every list of the best science fiction films. And it had all the necessary ingredients to do so: first contact with an advanced extraterrestrial civilization, a strong sense of wonder, and a more original approach than what Hollywood has accustomed us to in recent times.

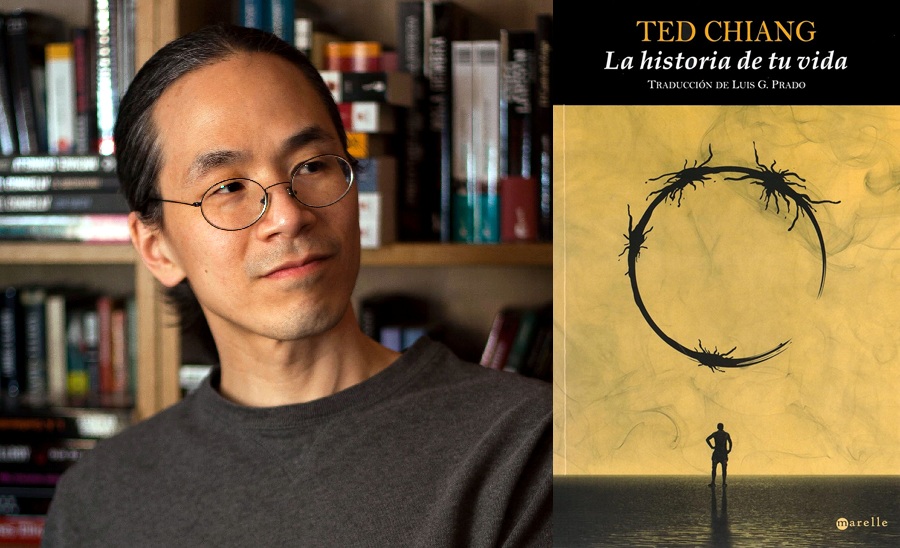

Based on Ted Chiang’s story “Story of Your Life,” we meet Louise Banks, a linguist who discovers the key to communicating with our visitors and whose perception of time is transformed as she learns the new language. However, the film, while not entirely forgetting it, doesn’t give as much importance to a detail that Chiang clearly considers crucial—and, in fact, is the seed from which the story was born: the scientific contribution and vision of Gary Donnelly (Ian in the film) is just as fundamental as Louise’s in achieving communication with the heptapods.

Ted Chiang has the wonderful habit of including, at the end of his anthologies—Story of Your Life and Exhalation—some notes about the ideas he later develops in his narratives, and this is what we find when he talks about how he came up with “Story of Your Life”; he writes it in the very first line: “This story was born out of my interest in the variational principles of physics.” He then goes on to explain various personal experiences, the role of Fermat’s Last Theorem in the plot, and the possibility of remembering the future, as Kurt Vonnegut explored in Slaughterhouse-Five. But what are these variational principles? And, above all, what do they have to do with time that would have given rise to a story like this?

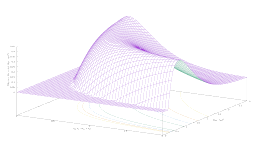

Calculus of Variations

The calculus of variations is a branch of mathematical analysis whose objective is to find functionals—or functions whose domain is a set of functions, rather than a set of values—that make a quantity extreme, that is, that make it minimum or maximum. It is applied to problems such as: what is the shortest path between two points? And the fastest? Or, among all the functions that describe a system, which one minimizes the energy used? It is the type of calculation used to determine a certain route on a GPS—the shortest, the fastest, or the most efficient—in industrial design and architecture—to calculate, for example, the minimum amount of materials—, aeronautics, economics—investment optimization—, medicine—calculation of minimum doses—and even machine learning.

One of the most popular applications of the calculus of variations is Fermat’s principle, which states that the path a beam of light will take to travel from one point to another will be the one that takes the least amount of time—which is not necessarily always the shortest (imagine we’re on the beach and want to reach a buoy offshore as quickly as possible. For a good runner, the fastest route would be primarily on land. A good swimmer, on the other hand, would try to run as little as possible and swim as far as they could. It’s about finding a balance between the two abilities). And here’s the thing: “…light can’t just start traveling in any direction and make corrections later. Because the resulting path won’t be the fastest possible. Light has to do all its calculations at the very beginning,” explains Ted Chiang, as told by Gary Donnelly. It’s as if the beam of light already knows in advance where it has to go, as if it already knows the trajectory it’s going to follow from the very first moment… as if it can see the future.

Initially, there would be no problem expressing virtually all of fundamental physics using the calculus of variations—except that doing so might make our lives miserable by forcing us to perform calculations that are much simpler using conventional methods. If we were a species that perceived time “as a whole,” without distinguishing between past, present, and future, it would surely be far more intuitive to do it this way… like the heptapods. In the story, which places much more emphasis on this point than the film, Fermat’s Last Theorem is what helps Louise unlock the key to the heptapods’ language, or at least how they understand the world. And it’s what allows her to understand why, as she learns the language, she begins to have visions of her future.

Bibliography

Bibliografía

Chiang, T. (2017 [2002]). La historia de tu vida (The story of your life). Alamut.

Feynman, R. (2006 [1963]). The Feynman lectures on physics. Vol. I: Mainly mechanics, radiation and heat. Basic Books.

Villeneuve, D. (Director). (2016). Arrival [Film]. Paramount Pictures.