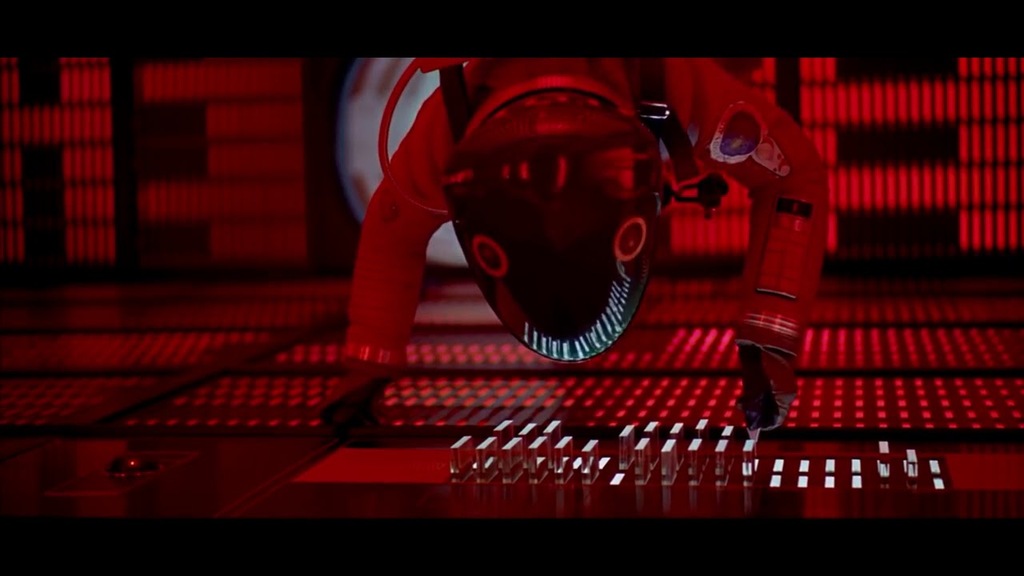

Astronaut Dave Bowman disconnecting HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The computer's last words are verses from the song Daisy Bell. Source: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer / Fair use.

This article was published in Spanish in the Cuaderno de Cultura Cientifica (CCC) under the title “Soy un computador HAL de la serie 9000…“, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Except for the English translation, no changes were made to the original article. Published with permission of CCC.

The author, Gisela Baños, is a science, technology, and science fiction communicator.

… I was put into operation at the HAL factory in Urbana, Illinois, on January 12, 1992. My instructor was Mr. Langley; he taught me a song. If you would like, I could sing it to you. It’s called Daisy.

This is the haunting farewell of HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey; surely one of the most… beloved? artificial intelligences in the world of cinema—HAL has its psychopathic tendencies, but I think, deep down, we all have affection for him. As Dave Bowman disconnects memory modules, the computer, by this scene more human than the humans, loses its abilities. Its voice slows down, becomes deeper, and it shuts down to the sound of a song that, at first, seems to make no sense:

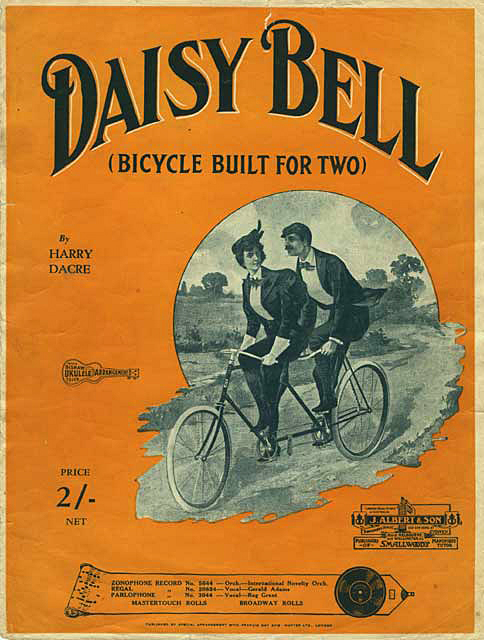

Daisy, Daisy, give me, give me your answer, do

I’m half crazy all for the love of you

It won’t be a stylish marriage

I can’t afford a carriage

But you’ll look sweet upon the seat

Of a bicycle built for two.

But it has it, and plenty of it. Years before the recording of 2001, in 1961, Daisy Bell had provided the soundtrack to one of the great milestones in the history of computing.

This rather naive song, in which a young man declares his love to his lady, dates back to 1892 and also has its story. On a trip to the United States, Harry Dacre, the author, decided to bring a bicycle with him, and when he tried to take it through customs, he was surprised to find he was charged duties. When he mentioned this to another composer and friend, William Jerome, Jerome remarked that it was a good thing it wasn’t “a bicycle built for two,” or he would have been charged double. The phrase apparently caught Dacre’s attention, and he decided to use it in a song: that song was “Daisy Bell.”

It was precisely the simplicity of the lyrics and melody, along with the fact that it was no longer under copyright at the time. This led electrical engineer—and violinist—Max Mathews and programmers John L. Kelly and Carol Lochbaum to choose it for the project they were undertaking at Bell Labs in Murray Hill. New Jersey. They wanted a computer to sing, or in other words, they wanted to digitize sound.

At Bell Labs, work had been underway on voice analysis and coding since the 1930s. The goal that engineer Homer Dudney had in mind when he created the vocoder in 1938 was to develop a device capable of analyzing and modifying speech signals to improve voice transmissions. He did so practically simultaneously with another device, the Voder, one of the first speech synthesizers—the result, to be honest, was rather sinister. Both inventions would be fundamental to the development of computer-based music coding.

Kelly was well acquainted with the intricacies of the vocoder, which he had worked with for a long time. Mathews, for his part, had created the first computer music generator program, MUSIC, in 1957. In the project to make a machine sing, Kelly and Lochbaum handled the vocals, while Mathews would synthesize the musical accompaniment with his software. The performer was a brand-new IBM 704 vacuum tube computer that operated with punched cards, and it sounded like this:

And now for the crossover! Max Mathews’ interest in computer music didn’t arise spontaneously; it was the idea of his boss, with whom he had a great relationship and with whom he occasionally went to concerts. In 1957, at one of those concerts, his boss suggested that Mathews pursue that line of work. This boss, as he once described himself, was “an obscure character” named John R. Pierce, who, coincidentally, was also a science fiction writer and a regular contributor to magazines like Astounding Science Fiction, where he often appeared under the pseudonym J. J. Coupling—a nod to physicists. As a science fiction writer, he was, of course, friends with other science fiction writers, including Arthur C. Clarke.

On one of Clarke’s trips to the United States in the early 1960s, Pierce invited him to visit Bell Labs. One of the star attractions of those tours for visitors was, of course, hearing the IBM 704 sing “Daisy Bell”… And the rest is cinematic history.

Impressed by what he had witnessed, Clarke included the song in the screenplay for 2001. Thus, in the scene where the computer loses its abilities as Dave disconnects it, HAL not only returns to its infancy but also to the infancy of the history of computing and artificial intelligence.

Bibliography

Clarke, A. C. (1980). The Lost Worlds of 2001. New American Library.

Hass, J. (s. f.) Introduction to computer music. Universidad de Indiana.

O’Dell, C. (2009). «Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)»—Max Mathews, John L. Kelly, Jr., and Carol Lochbaum (1961). Library of Congress.