(C) I-CON Srl - Use prohibited without written permission from I-CON

Eigen Artificial Neural Networks (EANNs) is a method for optimizing predictive systems in general, focusing on artificial neural networks. It was developed since 2019 by Francisco Yepes Barrera, although it only reached a theoretical maturity at the end of 2025, allowing for excellent results when applied to data sets present in the scientific literature. In this article, we explain the physical analogy underlying EANNs and how it constitutes the starting point for approaching the overfitting problem from a theoretical perspective.

In classical mechanics, stable configurations of physical systems are commonly associated with the minimization of an energy functional. In many physical contexts, the evolution of a system towards equilibrium can be described as a relaxation process, during which energy is dissipated until a minimum energy configuration is reached. This variational viewpoint has proven extremely effective in describing a wide range of macroscopic phenomena.

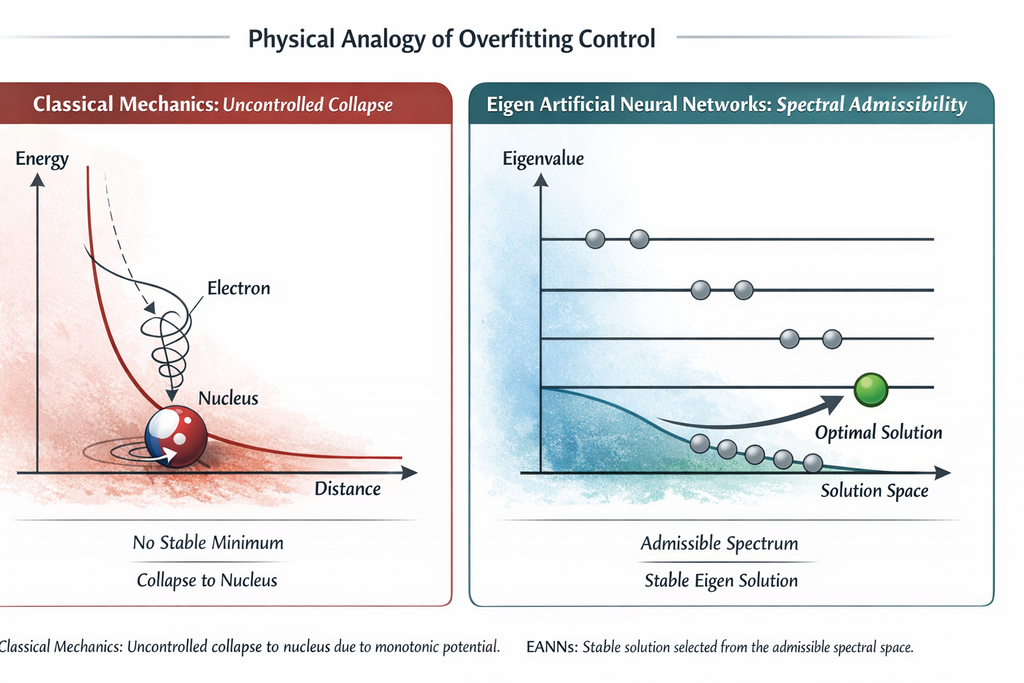

However, when applied to atomic systems, classical mechanics exhibits a fundamental limitation. Consider an electron interacting electrostatically with a proton. The Coulomb potential energy is a monotonically decreasing function of the electron-nucleus distance: between any two configurations, the one in which the electron is closer to the nucleus corresponds to a lower (more negative) potential energy. Consequently, classical mechanics provides no mechanism by which the system can reach a stable equilibrium at a finite distance. Furthermore, in classical electrodynamics, the electron accelerated by the Coulomb force continuously radiates energy; the system is therefore expected to evolve toward increasingly lower energy configurations, spiraling into the nucleus. The classical energy landscape presents no stable minimum, and atomic collapse appears inevitable.

Empirical observation of the stability of atoms has thus revealed a profound inadequacy of the classical description and motivated the development of a new theoretical framework. Quantum mechanics resolves this paradox not by introducing an external constraint or a repulsive force at short distances, but by reformulating the problem itself. Atomic structure emerges from the definition of a spectral operator—the Hamiltonian—whose eigenvalue problem determines the admissible physical states of the system. During atomic formation, the electron actually approaches the nucleus, and the total energy of the system decreases through energy emission until the system reaches the ground state, corresponding to the minimum eigenvalue of the Hamiltonian. The equilibrium configuration does not coincide with a minimum of the classical potential alone, but with a quantum-mechanically admissible state of the operator. As a result, the electron remains bound and close to the nucleus, but not arbitrarily close.

This distinction between classical energy minimization and quantum admissibility provides a useful structural analogy for understanding some fundamental limitations of machine learning models. In supervised learning, model evaluation typically relies on splitting the data into a training set and a test set. Reducing the training error improves the fit to the observed data, but, in the absence of additional constraints, this error can always be further reduced by increasing the model’s flexibility.

This observation is consistent with universal approximation theorems, starting with George Cybenko’s result and Kurt Hornik’s subsequent generalizations, which guarantee the existence of neural architectures capable of approximating any continuous function arbitrarily well on compact domains. These results, however, are purely existential in nature: they ensure the possibility of approximation, but they provide no intrinsic principle for selecting among the many solutions compatible with the training data, nor do they imply generalization properties.

Consequently, empirical risk minimization plays a conceptually analogous role to classical energy minimization: it identifies optimal configurations regarding a local criterion but does not impose global constraints on the solution structure. In the absence of such constraints, the learning problem admits a multiplicity of solutions equivalent in terms of training error, many of which exhibit poor generalization properties to unobserved samples, giving rise to the phenomenon of overfitting.

From this perspective, the introduction of structural or regularizing constraints can be interpreted as an admissibility principle, conceptually analogous to the constraints imposed by quantum mechanics on physically realizable states. Just as not all minimum-energy configurations are quantum-admissible, not all solutions that minimize empirical risk are statistically significant or generalizable. Effective learning, therefore, requires not only the optimization of a cost function but also the imposition of a selection principle that restricts the solution space to a structurally coherent class.

From an operational perspective, established empirical practice in machine learning has led to the development of a simple heuristic: among models that achieve equivalent performance on unobserved data, preference is often given to those with a slightly higher training error. This observation reflects the fact that models that overly aggressively minimize training error tend to overfit the data, resulting in increased variance and reduced robustness to new samples. It is important to emphasize that this heuristic does not imply that a high training error is desirable per se, but rather that uncontrolled minimization of empirical risk, in the absence of explicit regularization, provides no guarantee of improved generalization. From a learning theory perspective, among models with equivalent test performance, less complex solutions, or those less tightly fitted to the training data, should be preferred, reflecting an appropriate trade-off between bias and variance. In practical terms, this means that the selected model should closely fit the training data, but not excessively so, mirroring the EANN analogy discussed below, in which solutions are constrained to remain close to the data while avoiding overfitting, much as an electron in an atom remains close to the nucleus, but not arbitrarily close.

Eigen Artificial Neural Networks (EANNs) adopt a conceptually distinct strategy. Rather than modifying the loss function through explicit regularization, they reformulate the learning problem as a spectral problem. The training process is governed by an operator whose eigenvalue structure defines the space of feasible solutions. In this context, configurations that are excessively close to the data are not simply penalized a posteriori, but are excluded or severely constrained by the spectral structure of the operator itself.

In this sense, the role played by the spectral formulation in EANNs is analogous to that of the Hamiltonian operator in quantum mechanics. The analogy is not phenomenological, but structural: in both cases, it is the shape of the operator, not an external penalty, that determines the state space or feasible solutions. Just as atomic stability emerges from the structure of quantum eigenstates—resolving the unbounded collapse predicted by classical mechanics—generalization in EANNs arises from the geometry of the solution space induced by the eigenvalue problem. The learned model is constrained to remain close to the training data, but not arbitrarily close, while achieving fidelity and robustness.

From this perspective, the resistance of EANNs to overfitting can be interpreted as a form of implicit regularization that emerges naturally from the mathematical formulation of the model, rather than from ad hoc statistical penalties.

The figure in the header of this article illustrates this analogy, comparing the classical prediction of atomic collapse with the stable solution selected by an EANN, directly comparable to the stability of atoms explained by quantum mechanics.

References

Barrera, F. Y. (2019). Eigen Artificial Neural Networks. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.05200