Edoardo Bortoli - https://unsplash.com/photos/a-black-and-white-chess-set-on-a-checkered-board-pT_9rROIIAI

Sergey Smagin: A Soviet (later Russian) Grandmaster who reached his peak in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Known for a solid yet opportunistic style, he was a regular competitor in high-level European tournaments and attained a respected Elo rating of 2550 at the time of this game.

Dragutin Šahović: A Yugoslavian grandmaster and a well-known figure on the tournament circuit. He was recognized for his theoretical knowledge and professional approach to the game. Though rated lower than Smagin in this encounter, he was a formidable opponent capable of beating the world’s best on a good day.

The Biel MTO Open (1990) is part of the famous Biel Chess Festival in Switzerland. While the “Grandmaster Tournament” usually invited the absolute elite, the “MTO Open” was the premier open event, attracting a massive field of strong grandmasters and hungry youngsters. It served as a battleground where creative ideas were often tested against established theory.

By Round 10, fatigue often sets in during such a grueling open. Smagin, playing with the White pieces, likely prepared for a closed or semi-closed structure, knowing Šahović regularly preferred solid setups. The “eve” of this specific encounter involved Smagin looking for a way to crack the Nimzowitsch Defense, a somewhat provocative choice by Black that invites White to take the center.

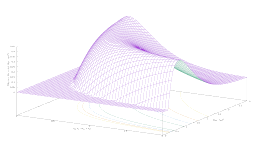

This game is a stunning example of how King safety and piece activity can outweigh a significant material advantage.

The game begins with the Nimzowitsch Defense (1. e4 Nc6), transitioning into a structure similar to the French Defense after 2. d4 d5 3. e5 Bf5 4. c3 e6. White establishes a strong central wedge. The engine notes that Black’s decision to open the center with 6… fxe5 was an inaccuracy (6), allowing White to solidify the e5 pawn and gain a space advantage.

The critical moment of the game occurs on move 12. Black plays 11… Ng5, pressuring the White pieces. Smagin ignores the threat to his Queen and plays 12. Nxg5, allowing 12… Bxd1.

By giving up the Queen for only two minor pieces (13. Nxe6 Qb8 14. Nxg7+ Kd8 15. Kxd1), Smagin calculated that Black’s pieces would be completely uncoordinated. The White Knights on e6 and g3 (later f5) dominate the board, while the Black Queen is trapped on b8.

Despite being up a Queen, Black is practically lost. The Knight on e6 is a “monster” that restricts the Black King and Rook. After 18. Rf1, Black tries to escape with 18… Kb7, but Smagin continues with the precise 19. Bh6.

When Black plays 19… Bxh6, he removes his only defensive minor piece. Smagin uses the Knight check 20. Nc5+ to force the Black King back to c8, and then occupies the hole on h6 with 21. Nxh6.

The final position is a tactical nightmare for Black. White’s Knights and Bishops control every vital square. After 23. Nf7, Šahović resigned. The Black Queen is a spectator, and the threats against the Black King and the impending loss of the Rook on h8 make the position indefensible.

Smagin proved that a Queen is useless if it has no squares and the rest of the army is disconnected. The Knights on c5, f7, and h6 acted as a cage, showcasing the “octopus” power of well-placed Knights. This game remains a classic example of the creative, high-risk chess often found in the Biel open festivals.