Osama Madlom - https://unsplash.com/photos/a-black-and-white-photo-of-a-chess-board-cShsbxi72CM

This bullet game between Stoofvlees and Igel was played on April 10, 2022, during the qualification rounds of the Chess.com Computer Chess Championship (CCC) 17. The CCC is an always-running computer chess tournament that pits the strongest chess engines in the world against one another in various formats, settings, and time controls.

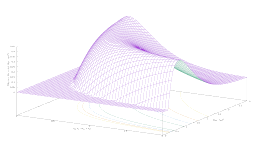

Stoofvlees is an experimental chess engine created by Belgian computer scientist Gian-Carlo Pascutto. The evaluation function consists of feature recognizers coupled to a neural network, which was trained with an oracle—the evaluation was entirely automatically learned from “watching” Grandmaster games. The results were incorporated into Deep Sjeng. In 2019, an updated version dubbed Stoofvlees II was announced, with neural networks instantiated on Nvidia GPUs. In 2023 and 2024, Pascutto won the World Computer Chess Championship organized by ICGA with Stoofvlees. Pascutto graduated from Hogeschool Gent in 2006 and has worked as a mobile platform engineer and manager at Mozilla Corporation since 2011. The name “Stoofvlees” is Dutch for “simmered meat” or “beef stew.”

Igel is a free UCI chess engine from Ukraine created by Volodymyr Shcherbyna. It started as a hobby project in early 2018 to learn chess programming and was forked from GreKo 2018.01. The name “Igel” is German for “hedgehog” and was chosen to represent numerous hedgehogs living in the creator’s garden. GreKo was chosen because it had clean code, supported Visual Studio, and was not a very strong engine, so further improvements would be possible. The first versions of Igel were actually regressions with less strength than the original GreKo, and after trying a few things and lacking experience in chess engine development, work was halted by late 2018. However, the engine made significant progress later. As of late 2020, Igel adopted NNUE (neural network evaluation) and uses its own NNUE implementation and own network file trained on Igel data.

The time control for this game was bullet—just 2 minutes plus 1 second increment per move—making this an extremely fast encounter between two neural network-powered engines. The opening was predetermined: the Nimzowitsch-Larsen Attack starting with 1.b3.

The game opened with the unusual 1.b3 e5 2.Bb2 Nc6 3.e3 d5 4.Bb5 Bd6, and White continued with 5.f4. According to the engine analysis, this move took the game out of opening theory. Black responded solidly with 5…f6, bolstering the center, and after 6.Qh5+ g6 7.Qh4 exf4, material was equal but the position had become sharp.

The game was developed with 8.Nf3 fxe3 9.O-O Bd7 10.Nc3 Nce7, and both engines maneuvered their pieces into active positions. White played 11.dxe3 c6 12.Bd3 Qc7 13.e4 O-O-O 14.exd5 cxd5, and the central tension was released. After 15.Kh1 h5 16.a4 a6, White pushed forward with 17.b4.

Black’s response, 17…g5, was considered inaccurate by the analysis, allowing White to seize the initiative. The tactical complications began with 18.Qf2 Bxb4 19.Nb5 axb5 20.axb5 b6, and White activated the rook with 21.Ra6 Kb7 22.Bd4 Nc8.

The position became increasingly complex after 23.c3 Ba5 24.c4 g4, and White made a critical decision with 25.Rxa5, sacrificing the exchange to maintain attacking momentum. After 25…bxa5 26.b6 Qd6 27.c5 Qc6 28.Nd2 a4, White had compensation for the material with dangerous passed pawns.

The game reached its climax with 29.Nb3 axb3 30.Ra1 Nd6 31.Ra7+ Kb8, and then came the powerful 32.cxd6 Qc1+ 33.Bf1. Black blundered catastrophically here with 33…Nh6, missing White’s tactical blow. The correct continuation would have been 33…Re8, keeping the position roughly balanced.

After 34.Qe2 Qc6 35.Qa6, White’s attack became overwhelming. The sequence 36.Qa2 b1=Q 37.Qxb1 saw Black promote a pawn, but White’s position remained dominant. Following 38.b7 Nxd6 39.Ra6 Nxb7 40.Rxc6 Bxc6 41.Bxf6, White had emerged with a decisive material advantage—a bishop and extra pawns in a simplified position.

The technical phase showed Stoofvlees’s precision. After 42.Kg1 Rh6 43.Bg5 Rdd6, White methodically improved the position with 44.Bf4 Re6 45.Qa1 Re4 46.Bg3 Ra4 47.Qh8 Kb6 48.Bxd6 Nxd6 49.Qxh5. White had consolidated the extra material and was winning easily.

The king marched forward: 53.Qd6 Re4 54.g3 Re8 55.h4 Rh8 56.Qf6 Rh7, and after 60.Ke3 Be4 61.Qf8+ Kc4, White’s advanced passed pawns became unstoppable. The climactic sequence came with 64.Qd6 Rh7 65.Kd4 Rh8 66.g6 Rxh6 67.Qb8+ Kc2 68.g7 Bh7 69.g8=Q Bxg8 70.Qxg8, and with two queens versus minimal material, the result was never in doubt.

The final moves demonstrated textbook technique: 71.Qf8 Rd7 72.Qf5+ Kd1 73.Qxd7 Ke1 74.Kxd5 Kf1 75.Ke4 Kg2 76.Qg4+ Kf2 77.Kd3 Kf1 78.Ke3 Ke1 79.Qe2#—checkmate.

Stoofvlees demonstrated the power of dynamic piece play and passed pawns, converting an exchange sacrifice into a crushing victory through precise calculation and technique. This game showcased exactly the kind of tactical brilliance that makes computer chess tournaments so compelling to watch.