This article was published in Italian in the newsletter DIRITTO ROVESCIO (Right Reverse) under the title “L’Avvocato Obsoleto”. Except for the English translation, no changes were made to the original article. Published with permission of Alberto Bozzo.

The author, Alberto Bozzo, is DPO and Chief Artificial Intelligence Officer, member of the IT and AI Commission at the Triveneta Union of Lawyers’ Councils (Italy).

In the United States, artificial intelligence is destroying the legal profession. Europe is watching. And waiting for its turn.

A New York lawyer is suing an airline. To bolster his arguments, he includes six case law references in his defense brief. They seem perfect: case numbers, names of judges, precise references. There’s just one problem. Those cases don’t exist. ChatGPT invented them. And the lawyer didn’t check.

This isn’t a joke. It’s the Mata v. Avianca case, May 2023. The first of an avalanche. Since then, over 600 cases have been documented in the United States of lawyers filing lawsuits fabricated by artificial intelligence. Nonexistent rulings, precedents never issued, and case numbers entirely invented. And the count is accelerating: while before spring 2025, two were registered a week, today two or three emerge a day.

This isn’t an article about technology. It’s an article about how a millennial profession is discovering its vulnerability. And what will happen when that same vulnerability crosses the Atlantic.

Table of Contents

The Hallucination Factory

Experts call them “hallucinations.” A stylish euphemism for artificial intelligence lying. Not out of malice, of course. Large language models—ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Copilot—are designed to be convincing, not accurate. When they don’t know the answer, they invent one. Confidently. In great detail. With that veneer of authority that fools even professionals.

“The more difficult your legal argument is to argue, the more the model will tend to hallucinate, because it will try to please you,” explains Damien Charlotin, a professor of AI law in Paris and curator of the database that tracks these incidents. “That’s where confirmation bias comes in.” The lawyer searches for a ruling that confirms his thesis. AI provides it. Too bad it’s made up.

A May 2024 analysis by Stanford’s RegLab revealed that some forms of artificial intelligence generate hallucinations in one in three queries. The problem isn’t marginal. It’s structural. It’s inherent in the very nature of these systems, which don’t “know” anything in the sense we understand it. They calculate probabilities. And when probability favors a plausible but false answer, they produce it without hesitation.

In the Mata v. Avianca case, attorney Steven Schwartz asked ChatGPT if the cited cases were real. The chatbot answered yes. It is even assured that “they can be found in authoritative legal databases like LexisNexis and Westlaw.” It was all false. But it rang true. And that’s the problem.

But here’s the paradox that should keep the profession awake at night: three out of four lawyers say they plan to use generative AI in their professional practice. The question isn’t whether they’ll use it, but how they’ll survive the damage they’ll cause by doing so.

The Silent Epidemic

The numbers tell a story of disturbing acceleration. The database maintained by Damien Charlotin documents the progression: from a handful of cases in 2023 to over 300 identified instances of AI hallucinations in court documents by mid-2025. Then the explosion. “Before this spring of 2025, we had maybe two cases a week,” Charlotin explains. “Now we’re at two or three cases a day.”

In California alone, 52 cases have been identified. Nationwide, over 600. And these are just the ones discovered. How many more have gone unnoticed? How many rulings have been influenced by nonexistent precedents? How many clients have lost cases based on arguments built on nonexistent foundations?

The most disturbing thing is that the phenomenon doesn’t just affect inexperienced lawyers or small-town firms. In the first two weeks of August 2025, three separate federal courts sanctioned lawyers for AI-generated hallucinations. One of them had used a popular legal research database—not ChatGPT, but a professional tool specifically designed for lawyers—which still produced fabricated citations.

“The transformation from ‘unprecedented circumstances’ to hundreds of documented failures represents more than a technological challenge,” writes one specialized law firm. “It’s an existential crisis for professional expertise.” When lawyers using Westlaw Precision—a tool specifically designed for legal research—still send out shocking citations, we must confront an uncomfortable truth: the problem isn’t just technology. It’s our total abdication of verification responsibilities.

The Price of Incompetence

American courts have lost patience. In September 2025, the California Court of Appeals fined Amir Mostafavi $10,000—the largest ever imposed on a lawyer in that state for misuse of AI. He had included 21 of 23 fabricated citations in his appeal briefs. Some cited decisions didn’t even discuss the issues for which they were cited. Others simply didn’t exist.

“The almost entirely fabricated citations and misstatements of law required this court to devote inordinate time to this otherwise routine appeal, attempting to trace fabricated legal authorities,” the judge wrote in his ruling. The lawyer was also reported to the state bar.

“I didn’t think ChatGPT was capable of creating false precedents,” another Chicago lawyer, dismissed after citing the nonexistent Mack v. Anderson case in a multi-million dollar lawsuit for the Chicago Housing Authority, justified herself. He even published an article on the ethical considerations of using AI in the legal profession. Ignorance is no longer a mitigating factor. It’s a confession of inadequacy.

In July 2025, a federal court in Alabama did something unprecedented in the Johnson v. Dunn case: instead of a fine, it disbarred the lawyers. It ordered the decision published in the Federal Supplement and reported those responsible to the professional bodies of every state where they were licensed. The message was clear: those who use AI without due diligence no longer deserve to represent anyone.

The law firm involved—large, respected, with internal policies prohibiting the use of AI without authorization—had conducted a systematic review of all its cases in Alabama’s federal courts and the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. It found no other cases of shocking citations. It even hired another firm for an independent audit. But the damage was done.

A Colorado lawyer caught denying the use of AI has accepted a 90-day suspension. The investigation found that he had texted a paralegal about fabrications in a motion ChatGPT had helped draft and, “like an idiot,” had failed to review the work.

But the most stinging blow came from California itself. In the case of Noland v. Land of the Free, the judge sanctioned the lawyer who had cited false cases but also refused to award the opposing party’s legal costs. The reason? They hadn’t noticed the fabricated citations and failed to report them to the court. In other words, reviewing your opponent’s work is becoming a professional duty. Spotting AI hallucinations may soon be part of the expected skills of every practicing lawyer.

The Collapsing Pyramid

Sanctions are just the surface. Beneath, the tectonic plates of the profession are shifting. For decades, large American law firms have functioned like pyramids: a few partners at the top, a mass of junior associates at the base. The latter bill hours on repetitive tasks—legal research, document review, due diligence—generating the cash flow that fuels the partners’ profits. It’s the “leverage model”: many juniors working, few seniors cashing in.

Generative AI is cannibalizing that base. “Is Big Law’s pyramid due to an AI makeover?” Reuters asked on December 11, 2025. The answer is yes. And the makeover has already begun.

The system has ensured stability and growth for decades, but its reliance on repetitive, time-intensive tasks makes it intrinsically vulnerable to new technologies. AI isn’t just a new tool. It’s a “digital architect” capable of demolishing and rebuilding the very structure of law firms. The pyramid isn’t disappearing. It’s getting thinner. The lawyers who remain will be more specialized, more strategic, and fewer. And the training pool? It’s simply drying up.

The firms that integrate AI not only to cut costs but also to create new value for clients through efficiency and sophistication of services will be the leaders of the legal landscape of the future. The others? They will be the dinosaurs of an era that is ending faster than anyone predicted.

The Race to Train (and its Foretold Failure)

American law firms are responding. Latham & Watkins launched a two-day “AI Academy” for first- to fourth-year associates. White & Case created a proprietary AI assistant called Atlas, designed to make reviewing work as easy as possible.

Barnes & Thornburg developed its own in-house version of ChatGPT, renamed ChatBT, and requires all lawyers to attend training courses on AI risks before using any tool.

But there’s a problem: AI training doesn’t work like training on any other technology. “AI doesn’t lend itself to the typical transactional exchange of information that has worked for previous technology implementations, starting with the introduction of email,” explains Kate Cain, director of insights and innovation at Sheppard Mullin. Tools are constantly changing. Risks are evolving. What worked yesterday may not work tomorrow.

White & Case has launched a program called “Trailblazers” for new associates: 20% of their billable time will be dedicated to AI training. “We think it’s critical. We think it will transform our practices,” says Jane Rogers, a partner at the firm. “Not only in terms of efficiency—that’s helpful and important—but it also allows us to provide better service to clients.”

But familiarity with AI tools isn’t everything. “Human verification is central to the responsible use of AI tools and their development,” emphasizes Isabel Parker, chief innovation officer at White & Case. The problem is that training people to verify takes time. And the market doesn’t allow for that.

“We want people to get to work, experiment, and try things out, but within their fiduciary responsibilities and ethical obligations,” says Kelly Mixon Morgan of Barnes & Thornburg. “I don’t think we’ve ever integrated at this level before.” Here’s the thing: no one’s ever had to do it before. And no one really knows how to do that now.

The End of Hourly Billing

“2026 could be the year that alternative fee arrangements take over hourly billing,” predicts a report from BTI Consulting and McKenna Associates. If AI can do in ten minutes what a junior lawyer could do in ten hours, why should the client pay for ten hours?

“It’s now a reality,” admits Colin Murray, managing partner of Baker McKenzie for the Americas. “We’re fully embracing it.” Sunny Mann, global president of Baker McKenzie, confirms that the connection between evolving AI use and law firm pricing is “one of the two most important themes that comes up in virtually every single client meeting.”

“In the next year or two, we’ll start to see a sea change not only because of the AI trend, but also because client thinking has evolved,” says Mann. “Many clients have historically tended to be quite tied to the billable hour calculation, because that’s how law firms tend to demonstrate the value of their services.” That world is ending.

The BTI and McKenna report notes that American firms, especially those with more standardized legal practices, may soon follow the lead of their European and Asian counterparts, who have embraced alternative fee arrangements in greater numbers. “Chief legal officers are becoming more vocal, proactive, and demanding, suggesting that 2026 could be the year when AFAs take over from hourly billing and fee pressures reach a breaking point.”

The challenge is culturally profound: abandoning the familiarity of hourly billing, which has historically provided predictable margins, in favor of a more complex and negotiated measurement of value. But when the alternative is irrelevance, even the most conservative adapt.

Literacy vs. Fluency: The New Career Divide

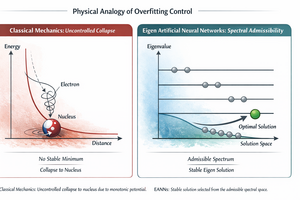

There’s an ongoing debate in the legal profession: what does it mean to be “competent” in the age of AI? The traditional answer is “literacy”—knowing what AI is, understanding that it can make mistakes, and being aware of the risks. But literacy isn’t enough. What’s needed is “fluency.”

The difference is fundamental. Literacy allows you to use AI. Fluency allows you to work with AI as a partner—shaping it, controlling it, and improving it to achieve results that meet legal standards. Literacy is reactive: it equips you to use a tool, but not necessarily to decide how it should be used in a workflow, to recognize deeper failure modes, or to improve the system when it doesn’t work.

A “fluent” lawyer doesn’t just evaluate the output. They structure the input strategically: they draft well-structured prompts, provide relevant context, select authoritative sources, configure search, and iterate based on the system’s behavior. He understands why a model might be delusional, why citations might be incomplete, and how to guide the process toward verifiable results.

The problem is that most lawyers aren’t even literate, let alone fluent. And the training they’re receiving—when they receive it—stops at literacy. “If we train lawyers only for ‘awareness’ where ‘workflow design and critical review’ are required, we undermine quality, compliance, and ultimately trust in legal AI.”

What emerges is a spectrum of expertise, not a binary. Literacy is necessary for all; fluency is essential for many; and a substantial middle ground exists where lawyers don’t code but must actively operate, critique, and improve AI workflows. By losing this nuance, the profession risks producing users who know how to click but not how to control.

The Judges’ Consortium: When the Judiciary Organizes Itself

On January 23, 2026, several U.S. federal judges—including U.S. Magistrate Judge Maritza Dominguez Braswell of the District of Colorado and Judge Scott Schlegel of the Louisiana Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit—announced the launch of the Judicial Artificial Intelligence Consortium (JAIC). This organization, led by judges and for judges, aims to shed light on the use of artificial intelligence in the chambers and courtrooms.

“The newsletter was born out of this desire to share information and resources, but as I reflected on the relative impact of all this, I thought there had to be a better way to do it, to share and learn,” Judge Braswell explained. “I thought to myself, wouldn’t it be great if we were all in the same space talking about this and tackling these issues together?”

The very fact that judges feel the need to self-organize to understand a technology that already impacts the cases they adjudicate is a warning sign, not a sign of progress. “It’s important for judges to collaborate with professionals and vice versa, but there aren’t many spaces where this is truly judge-only and judge-only across all jurisdictions,” Braswell said. The JAIC will create “a sense of camaraderie and comfort that will foster much more candid dialogue.”

The JAIC’s first meeting, scheduled for February 25, 2026, aims to address judges’ questions as a forum for constructive dialogue. But the underlying question remains: if even judges don’t know what to do with AI, who should?

Europe that watches

Now the awkward question: are Italy and Europe immune? In the United States, 42% of law firms and in-house teams report using AI technology. 85% have created dedicated resources or committees to manage AI implementation. 56% predict AI will become a widespread technology in the legal industry within five years. 77% expect increased use in the next five years.

And Europe? In Italy, only 36% of lawyers report using AI in their professional practice. This means 64% aren’t using it—yet. When they start, they’ll make the same mistakes. Not because Italians are less competent than Americans. But because the factors causing American disasters are universal: cost pressure, the speed of technology adoption, and the unpreparedness of practitioners.

In our country, we already have a Vademecum from the National Bar Council on the use of AI, updated with references to EU Regulation 2024/1689 (AI Act), Law 132/2025, the CCBE Guidelines of October 2025, and the Council of Europe Convention on AI and Human Rights.

Article 50 of Professional Law 247/2012 provides disciplinary sanctions for those who cite unverified sources. The regulatory framework exists.

But have Italian courts ever sanctioned a lawyer for AI-generated citations? Not yet. And this silence is not reassuring. It’s the prelude to an explosion.

The Italian Vademecum: Dead Letter or Preventive Shield?

The National Bar Council’s “Brief Handbook for Lawyers on the Use of Artificial Intelligence” is a serious document. It lists general principles: legality, fairness, transparency, and responsibility. It reiterates that AI is a support tool, never a substitute for human judgment. Each output must be checked, revised, and confirmed as the professional’s own. Responsibility for the document remains entirely with the lawyer.

The operating instructions are precise. Before use, choose professional platforms that comply with European regulations, familiarize yourself with the terms of service and privacy policies, and understand the system’s operation and limitations (including the risk of “hallucinations”). During use: anonymize data, avoid public chatbots for texts containing confidential data, and formulate clear and targeted questions. After use, verify all regulatory or case law requirements in official databases, and personally revise the text.

The behaviors to be avoided are clearly listed: citing legal sources, rulings, or doctrines generated by AI without careful review; entrusting the entire drafting of documents or contracts to AI; entering personal data or professional secrets into public chatbots; using automatically generated texts without human review; and attributing errors or inaccuracies to AI for justification.

The disciplinary consequences are clear: reporting to the Bar Council, disciplinary proceedings before the District Disciplinary Council, and sanctions ranging from warning to censure, suspension, or expulsion, depending on the severity of the offense.

The Augmented Jurist (or the Euphemism for Fired)

There’s a comforting narrative circulating at conferences: the lawyer of the future will be an “augmented lawyer,” a professional who uses AI to free themselves from repetitive tasks and focus on strategy. Partners and senior associates will have to spend less time reviewing basic work and more time analyzing AI-generated output, focusing on strategy, complex negotiations, client relationship governance, and the application of human judgment in borderline situations.

It’s true. But it’s also a half-truth that hides a more unpleasant truth. If AI does the work of twelve lawyers, twelve lawyers aren’t needed. One lawyer is needed to supervise the AI. The other eleven don’t become “augmented.” They become superfluous.

The lawyers of the future will be “augmented lawyers,” yes—professionals who not only understand the law but can also effectively interact with and supervise AI systems. The ability to ask the algorithm the right questions, critically interpret its results, and assume ethical and legal responsibility for using technology will become the most valuable skills. And, consequently, the most expensive.

The rise to partnership will become even more arduous, reserved only for those who demonstrate excellence in strategic consulting and business development, no longer based simply on the endurance of the sheer number of hours worked. Those entering the profession today should ask themselves, Will my role still exist in ten years?

Big Tech Attacks

Anthropic—the company that makes Claude—has just released a legal plugin for its Cowork product. It promises to review documents, report risks, and monitor compliance. It’s one of eleven announced plugins, designed for non-programmers. In other words, for lawyers who don’t want to learn to code but still want to use AI.

“Anthropic’s recent foray into the legal sector could represent a radical change for the legal tech ecosystem,” writes Legaltech News. Claude’s legal plugin promises to perform tasks—such as document review—already offered by specialized startups like Harvey and Legora. If law firms or legal teams already use Claude or have an enterprise license, the addition of the legal plugin offers them less incentive to invest in legal tech startups with similar offerings.

“Consumers of legal services could use the tool to avoid or circumvent requests for legal advice,” warns Brad Blickstein, CEO of the Blickstein Group. This isn’t alarmism. It’s a description of what’s already happening.

Ed Walters, vice president of legal innovation and strategy at Clio, doesn’t see this as a threat to legal service providers. “Having tools available to consumers is really better than nothing,” he says. “People who represent themselves, and occasionally those are small businesses… Having some legal support and legal assistance is better than nothing. I also want to be careful to say that consulting Claude shouldn’t be the end of the process, but the beginning.”

But here’s the truth no one wants to say: Big Tech doesn’t build legal tools to help lawyers. They build them to make lawyers less necessary. Every plugin, every automation, every “efficiency” is a brick removed from the edifice of the profession. And lawyers themselves are paying to have it removed.

From Individual Dependence to Systemic Dependence

“The Mata v. Avianca incident exposed the real risks of algorithmic dependence—a lawyer trusted machine output instead of professional judgment, leading to sanctions and reputational damage,” writes a law firm specializing in AI.

“Informal surveys indicate that a significant percentage of litigators now rely on AI tools for legal research. And, increasingly, many of them fail to verify sources.”

This dependence undermines the traditional expectation that professionals can conduct, analyze, and verify their own work. The transformation from an “unprecedented circumstance” to hundreds of documented failures represents more than a technological challenge. It is an existential crisis for professional expertise.

As AI becomes essential infrastructure for professional practice, the challenge is not avoiding AI dependence but consciously managing it. The way forward requires more than policies and procedures. It requires a fundamental commitment to the principle that makes us professionals: we, not our tools, bear the ultimate responsibility for the integrity of our work. Whether this work emerges from hours in a law library or seconds of AI processing, the signature on the document remains human.

The Question No One Wants to Ask

“Meanwhile, there will be victims, there will be damage, there will be debris,” admits Mostafavi, the Californian lawyer fined for fabricated citations. “I hope this example helps others avoid falling into the pit. I am paying the price.”

America is paying the price. Europe is watching. But watching is not learning. Learning means acting before disaster strikes. It means training before sanctioning. It means regulating before the market decides for everyone.

“Our 2025 survey shows that legal technology and artificial intelligence have reached mainstream status,” concludes an industry report. “In 2026, success will depend on how well the tools are integrated, how secure they are, and how effectively teams are trained to use them.” In other words, those who don’t adapt disappear.

Italian lawyers can tell themselves that things are different here. That we have the AI Act. That we have the Code of Ethics. That we have a culture of verification. But the numbers don’t lie: three out of four lawyers will use AI. One in three will blow its mind. And when the first Italian case of a fabricated subpoena hits the headlines, we’ll find we were warned.

“We’ve passed the tipping point,” writes legal industry analyst Ari Kaplan, after interviewing 32 professionals and collecting data from 112 people across law firms and corporate legal departments. “Amid intense competition and shifting client expectations, it’s clear that lawyers are actively preparing for an AI-driven future of litigation.”

The future of legal AI won’t be defined by technology alone, but by the legal profession’s ability to use it wisely, critically, and creatively. Those who invest in building these capabilities now will not only avoid risks but will shape the workflows, institutions, and legal services of the next decade.

The question isn’t if it will happen. It’s when. And who will pay. At the root, however, let’s ask ourselves why a lawyer should use Artificial Intelligence.

Bibliography

Mata v. Avianca, Inc., Southern District of New York, maggio 2023

Johnson v. Dunn, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, luglio 2025

Noland v. Land of the Free, L.P., California Court of Appeals, settembre 2025

Reuters, “Is Big Law’s pyramid due an AI makeover?”, 11 dicembre 2025

Stanford RegLab, “Large Legal Fictions: Profiling Legal Hallucinations in Large Language Models”, maggio 2024

BTI Consulting Group & McKenna Associates, Report sugli studi legali, 2025

Damien Charlotin, Database AI Hallucinations in Legal Filings (600+ casi documentati)

Law.com/Legaltech News, “AI Boom Forces Law Firm Tech Leaders To Rethink Training Practices”, 4 dicembre 2025

Law.com, “It’s Real Now: With Law Firm AI Use on the Rise, Expect Alternative Fee Arrangements to Pick Up Steam in 2026”, 18 dicembre 2025

Law.com, “Claude’s New Legal Plugin Could Threaten Dominance of Legal Tech’s AI Leaders”, 3 febbraio 2026

Law.com, “Legal Organizations’ AI Use Matured in 2025—That Momentum Isn’t Stopping”, 1 dicembre 2025

Law.com, “In-House Teams Are Prioritizing Technology Strategy in 2026”, 8 dicembre 2025

Law.com, “Planning for an AI-Centric Litigation Future: Unfiltered Insights on the State of the Legal Profession”, 30 gennaio 2026

Law.com, “Judicial AI Consortium Aims to Set the Record Straight on AI in Courts”, 28 gennaio 2026

Stefan Eder, “AI Literacy, AI Fluency and the Changing Skill Set of Lawyers”, Legal Informatics Newsletter, 7 dicembre 2025

Stefan Eder, “The Legal Workstation: A Vision of How Legal Work Will Be Organised in the Near Future”, 21 dicembre 2025

Consiglio Nazionale Forense, “Breve Vademecum per Avvocati sull’utilizzo dell’Intelligenza Artificiale”, 2025

Regolamento UE 2024/1689 (AI Act)

Legge 23 settembre 2025, n. 132 (Italia)

CCBE, Guida sull’uso della Gen AI, 2 ottobre 2025

US Legal Support, “Litigation Support Trends Survey 2026”, 20 novembre 2025

Harbor & CLOC, “Law Department Survey 2025”, dicembre 2025

ABA Formal Opinion 512 – Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools, 2024

Jones Walker LLP, “From Enhancement to Dependency: What the Epidemic of AI Failures in Law Means for Professionals”, 2025

Cronkite News, “As more lawyers fall for AI hallucinations, ChatGPT says: Check my work”, 28 ottobre 2025

CalMatters, “California issues historic fine over lawyer’s ChatGPT fabrications”, 22 settembre 2025