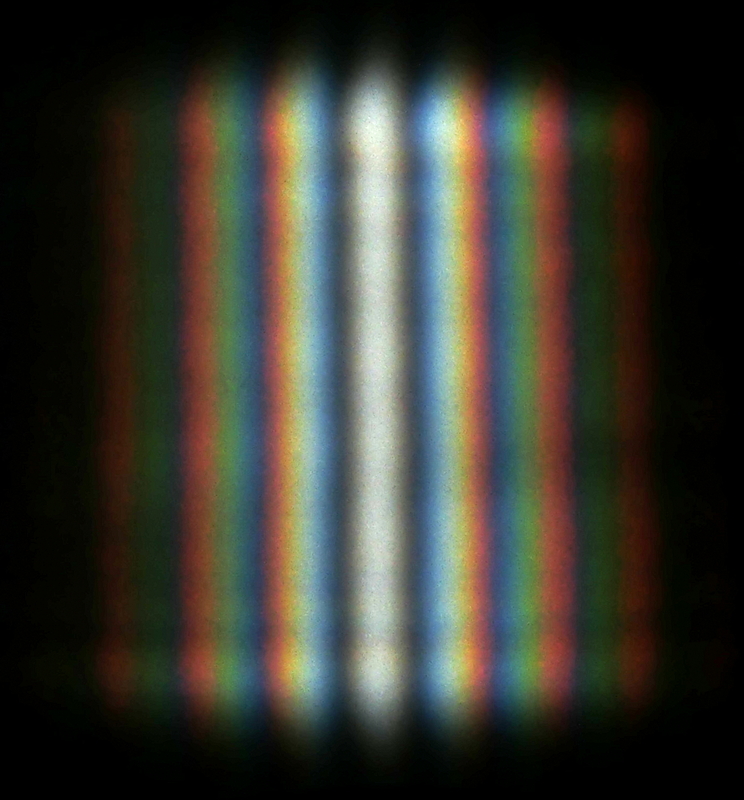

Interferencia de un experimento de doble rendija empleando luz solar. Fuente: Aleksandr Berdnikov CC BY-SA 4.0 / Wikimedia Commons.

This article was published in Spanish in the Cuaderno de Cultura Cientifica (CCC) under the title “El experimento de la rendija móvil de Einstein–Bohr, con un solo átomo” under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Except for the English translation, no changes were made to the original article. Published with permission of CCC.

About the author: César Tomé López is a science communicator and editor of Mapping Ignorance.

In the late 1920s, at the height of the development of quantum mechanics, Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr engaged in one of the most influential debates in the history of physics. At the heart of the Einstein-Bohr discussion was a question as simple as it was profound: would it be possible to simultaneously observe the wave-particle duality of a quantum particle? At the 1927 Solvay Conference, Einstein proposed a thought experiment, now known as the Einstein-Bohr moving-slit experiment, with which he intended to challenge Bohr’s principle of complementarity. Almost a century later, recent research has succeeded in replicating this experiment with unprecedented fidelity, using only a single atom and a single photon.

To understand the significance of this work, it’s helpful to recall the classic double-slit experiment. When light is passed through two narrow slits, a characteristic interference pattern appears. However, if you try to determine which slit each photon passes through, this pattern disappears. Bohr interpreted this as a manifestation of the principle of complementarity: the wave nature and the particle nature are mutually exclusive descriptions that cannot be observed simultaneously in the same experiment.

Table of Contents

Gedankenexperiment

Einstein was not satisfied with this conclusion. He proposed imagining one of the slits mounted on a movable support so that when a photon passed through, the slit (its support) would experience a tiny recoil. If this recoil could be measured with sufficient precision, it would, in principle, allow the photon’s path to be reconstructed without destroying the interference pattern. The key lay in the exchange of momentum between the photon and the slit. Bohr responded by pointing out that, by making the slit movable, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and the quantum fluctuations of the support itself come into play, preventing the simultaneous acquisition of both pieces of information.

For decades, the Einstein-Bohr experiment remained in the realm of ideas (what is known as a Gedankenexperiment, or thought experiment) because it was not clear how it could be physically carried out. The main obstacle was one of scale: a macroscopic slit has a much greater uncertainty in linear momentum than the momentum of a single optical photon. Under these conditions, the recoil is undetectable. The new work solves this problem by replacing the slit with the lightest possible object that can be manipulated in a controlled manner: a single atom.

A Slit That Is an Atom

In the experiment, researchers use a rubidium atom trapped by optical tweezers—a very intense laser beam that acts as a microscopic trap. Using advanced laser cooling techniques, the atom is prepared in its ground state of motion, meaning its quantum fluctuations in position and momentum are at the limit imposed by quantum mechanics. In this regime, the uncertainty in the atom’s momentum is comparable to the momentum of a single photon, something completely beyond the reach of macroscopic systems.

The atom thus acts as a moving quantum slit. When a photon strikes it and is scattered, the atom experiences a recoil whose sign depends on the direction from which the photon is scattered. The photon and atom then become entangled: the state of the former is correlated with the momentum of the latter. The visibility of the interference observed in the photon depends directly on how much the possible states of motion of the atom overlap after the recoil. If these states are almost indistinguishable, the interference is clear; if they are distinguishable, the interference is lost.

Adjustable Uncertainty

A particularly elegant aspect of this version of the Einstein-Bohr experiment is that researchers can continuously adjust the atom’s momentum uncertainty by varying the depth of the optical trap. By confining the atom more tightly, its spatial uncertainty is reduced, and, as a direct consequence of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, its momentum uncertainty increases. This results in a gradual transition from a regime dominated by the photon’s wave-like behavior to one where trajectory information becomes accessible, and interference disappears.

Furthermore, the experiment allows researchers to clearly distinguish between purely quantum effects and classical effects due to the atom’s heating. When the atom absorbs energy and leaves its ground state, the loss of interference is no longer due to quantum entanglement but to thermal noise of classical origin. This distinction provides a clear view of the transition between the quantum and classical worlds.

Internal Coherence of Quantum Mechanics

The physical realization of the Einstein-Bohr experiment not only confirms, once again, the internal consistency of quantum mechanics but also translates the core of the old debate into modern language. Today, we understand that the visibility of interference patterns is governed by the degree of entanglement between the observed system and the measuring device. Far from being a technological limitation, complementarity emerges as a profound consequence of the quantum structure of nature. This work demonstrates, with a clarity difficult to imagine a century ago, that the Einstein-Bohr discussions were not about technical details, but about the very way in which reality manifests itself when we observe it.

References

Referencia:

Yu-Chen Zhang, Hao-Wen Cheng, Zhao-Qiu Zengxu, Zhan Wu, Rui Lin, Yu-Cheng Duan, Jun Rui, Ming-Cheng Chen, Chao-Yang Lu & Jian-Wei (2025). Tunable Einstein-Bohr Recoiling-Slit Gedankenexperiment at the Quantum Limit Phys. Rev. Lett. DOI: 10.1103/93zb-lws3

To Learn More

Tomé López, C. (2013). Incompletitud y medida en física cuántica Cuaderno de Cultura Científica

Tomé López, C. (2019). Cuantos. Cuaderno de Cultura Científica