Barry Weatherall - https://unsplash.com/photos/white-chess-pieces-on-chess-board-zUnObqRg6s8

This game is one of the most celebrated encounters in chess history, a legendary battle from the 1834 match between the two greatest players of the early 19th century.

Alexander McDonnell, The strongest player in Great Britain. An Irish master with a tenacious, deeply analytical approach, he was the only player capable of challenging the French master’s supremacy.

Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais, the unofficial world champion from France. A nobleman who lived for chess, he was known for his incredible speed of play and his overwhelming attacking style.

The marathon series of matches held at the Westminster Chess Club in London in 1834 was the first truly great international chess contest. There was no official “World Championship” at the time, but the public treated this as such. By the Fourth Match, the players were exhausted but intimately familiar with each other’s styles. McDonnell was constantly trying to find ways to break the Frenchman’s defense, while La Bourdonnais relied on his intuitive grasp of central control—a concept he pioneered long before it was formally codified.

This game is famously known as the “Immortal 16th Round” of the fourth match. It features one of the most iconic final positions in chess history. The game began with an early version of the Sicilian Defense (1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6). McDonnell chose an aggressive setup, but La Bourdonnais quickly established a solid central presence with 4…e5 and 8…d5.

White missed several opportunities to maintain equality, notably with 12.exd5?! and 14.c4?!, which allowed Black to build a powerful center. The game reached a fever pitch around move 21. McDonnell attempted to complicate things with the tactical shot 22.Ba4, but La Bourdonnais responded with the cold-blooded 22…Qh6!, ignoring the Rook to focus on the King.

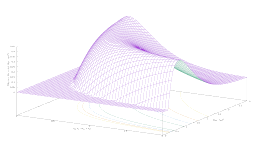

The defining moment of the game is the advance of Black’s central pawns. Following a series of sacrifices, La Bourdonnais steered the game into a position where his passed pawns became a force of nature: 28…d3! pushed the dagger deeper, while 33…d2! and 35…e3! created a phalanx that the White heavy pieces could not stop.

The final position is legendary: Black has three connected passed pawns on the second rank (f2, e2, d2).

McDonnell was completely paralyzed. After 37…e2, White resigned. The “Triple Pawn” finish remains the ultimate symbol of the power of the center.

Analyzing the specific moment on move 26 is fascinating because it reveals how close McDonnell was to surviving the “pawn avalanche.”

In the game, McDonnell played 26.Kh1?, which was the losing mistake. The engine shows that 26.Rf2! would have held a draw (0.00). By playing 26.Rf2, White creates a solid blockade. The Rook on f2 directly stops the f-pawn from promoting and defends against the immediate checks. If Black tries to continue the attack with 26…Bc8, White has enough time to play 27.Bd7, neutralizing the powerful Bishop and keeping the center closed just enough to survive.

Instead, after 26.Kh1?, La Bourdonnais was able to push his pawns with no resistance. Let’s look at the final summary of that historic march:

- Move 31…Bd8!: A deep defensive and offensive move, preparing to shield the King while the pawns march.

- Move 33…d2!: The first pawn reaches the “rank of fire.”

- Move 37…e2!: The final blow.

It is said that McDonnell was so traumatized by the sight of these three pawns that he had nightmares about them. In the 19th century, seeing a King and two Rooks completely helpless against three simple pawns was a revolutionary concept.