Lucas Pezeta - https://www.pexels.com/photo/close-up-photo-of-giraffe-2575702/

AI now pervades our work. Many of the techniques we use are based on physical or biological mechanisms. However, their uncritical use can prevent us from grasping some interesting nuances. If these are not directly essential for practical applications, placing ourselves in the appropriate context can indeed allow us to use them properly and with their maximum potential. The epistemological aspects of our tools, even if they are algorithms that run on a computer, must always be taken into account.

An example is genetic algorithms, techniques that attempt to imitate biological evolution by natural selection and that are used in a very specific type of mathematical problem: optimality problems. When we have a complex industrial issue in which we need to find a maximum or a minimum, genetic algorithms are the right thing to use.

When Darwin published his theory in the mid-1800s, evolution was not a new concept. Lamarck anticipated it by half a century. The latter proposed the “inheritance of acquired characteristics” through “use and disuse” (the giraffe has a long neck from trying to reach the highest leaves of the trees). Characteristics acquired during the life of an individual are transmitted to descendants. This vision is in contrast with the Darwinian theory, based on inheritance at birth, and was supplanted by it. The further integration, now in the 1900s, of Mendel’s laws (which had been forgotten for almost 40 years) gave rise to modern neo-Darwinism.

There is an interesting aspect to Lamarckism. Although not directly introducing finalist concepts, Lamarck believed that organisms tended to evolve towards greater complexity and organization due to an “internal impulse” to life, which pushed them to become more “perfect” and adapted to their environmental conditions. A teleological vision.

It is difficult to criticize Lamarck too harshly for this. Since Paracelsus and even before, finalism and vitalism were inherent in European culture, all mixed with religious aspects in the worldview, and Lamarckism is a reflection of this. Lamarck rejects theological issues and creates a complete and powerful theory. Lamarckism is supposed to be a giant step forward in the understanding of biological mechanisms. His errors are largely the result of the historical and cultural context in which he lived.

The superiority of Darwin’s theory comes from the understanding that the teleological aspects of evolution are unnecessary. As long as a limiting mechanism is introduced: the “selection pressure.” When the resources available are not sufficient for everyone but only for some, then a competitive mechanism emerges autonomously that makes the population evolve: natural selection. An evolution, therefore, without a pre-established direction.

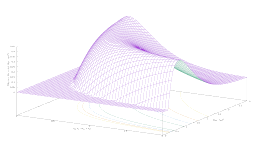

Genetic algorithms are a way of solving problems inside a computer by recreating, on a small scale, natural selection. Anyone who has designed and tested one knows that there is no explicit purpose in the calculation program. Provided that we introduce selection pressure, which in genetic algorithms is given by maintaining a fixed number of individuals in the population (only some can live), and a way to evaluate the degree of adaptation of each solution. Then, a competitive mechanism appears autonomously that makes the population evolve towards the optimum.

This qualitative discussion that we have had was solidly founded by the wonderful work of John Henry Holland in the 70s: “Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems,” 1975. A mathematization of evolution for algorithmic purposes.